Kidnapped (2023), directed by Marco Bellocchio, is a powerful historical drama based on the true story of Edgardo Mortara, a Jewish child forcibly taken from his family in 1858 by the Papal States after a secret baptism.

The film delves into themes of faith, identity, and family, portraying the harrowing struggle between religious authority and personal freedom. With Bellocchio’s masterful direction, Kidnapped offers a gripping exploration of a dark chapter in history that resonates deeply today.

I had the privilege of working on the film, which won a David di Donatello (essentially Italy’s Academy Award) for scenography, thanks to the stunning work of Andrea Castorina. Our goal was to digitally reconstruct the Tiber harbor by Ponte Elio, aided by a practical set for the first building. It was one of my first on-set experiences, and it was truly eye-opening and fun—what a collective effort filmmaking is! My task was to set-extend Rome with a sizable CG extension, as the practical set was shot in a remote location, still along the Tiber River but near Poggio Mirteto. As a Roman and a history buff, this kind of effect was my jam!

I began researching vistas from 19th-century painters, particularly the master Ettore Roesler Franz, one of my favorite landscape artists. I got lucky that the scene’s perspective, as envisioned by the scenographer and director, was quite popular and well-documented in the 19th century.

I have to thank the page info.roma, a true treasure cave of culture and references for self-taught researchers like myself.

I discovered a priceless document in a collection of photos recently auctioned—possibly the oldest known photograph of Rome. These images still show the old 17th-century Teatro Apollo, or Teatro Tordinona, once one of the most vibrant theaters in the city, sadly demolished during the construction of the new Tiber walls in 1888. A similar fate befell the ancient Hospital of Santo Spirito in Saxia, originally built in the 8th century CE. The hospital’s facade was set back during the construction of a road in front of it. This makes sense considering that the early Italian legislation was strongly anti-clerical, aiming to diminish the Church’s influence through urban interventions.

It was an indescribable experience to bring to life what no longer exists, resurrecting old photographs of long-forgotten parts of the city. Rome’s intricate and complex nature continues to amaze me. I find a special beauty in this type of VFX, as it allows me to uncover the history behind things I once took for granted. For example, I was amazed to discover that Castel Sant’Angelo had a clock on top from 1746 to 1934—something I never knew until I started working on and researching these assets!

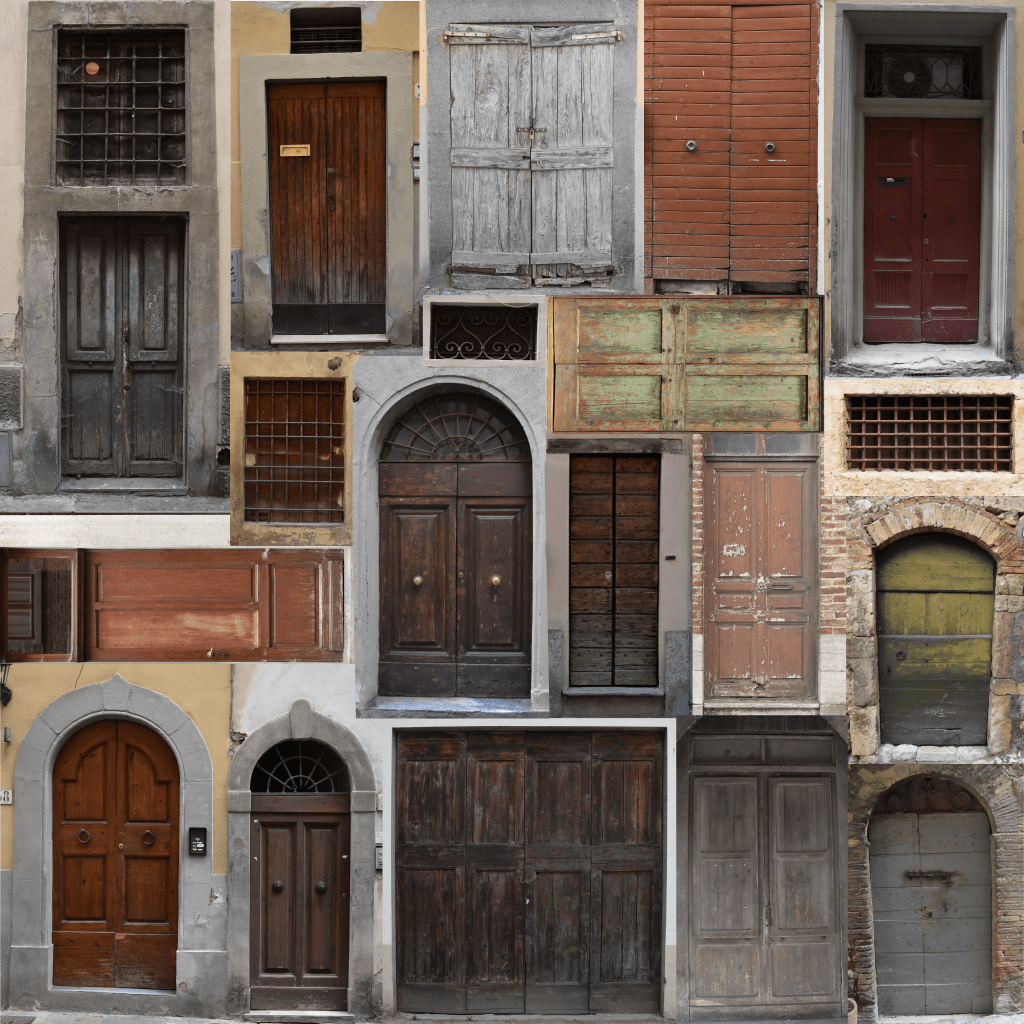

On a different note, here are some texture atlases I created using my own photos and on-set materials. This approach has been highly effective: it allows for seamless integration of CG elements with real props, and my passion for photographing historical buildings and doors has provided me with a rich library of textures to draw from.

This approach also aids in file optimization by reducing the number of textures needed, keeping even large CG projects like this one manageable and CPU-efficient.

I’d love to update this page periodically, sharing photos I take of this part of Rome as it looks today. If you find it interesting, feel free to visit from time to time—who knows, this could evolve into a series of historical reconstructions of the Eternal City I grew up in.